by Woodsbum

Today I ran across an interesting article on the .300 Weatherby. For many years I have used mine mainly for elk and even reload for it. The rifle and cartridge has worked well for me once I got it all dialed in with a solid load. Recently I was able to get everything figured out where I am hitting the same spot time after time at 100 yards (of course strapped to a lead sled) with some 180 grain bullet loads. The truth is that I am now quite fond of both the rifle and the cartridge.

Unfortunately, there has been a lot of “bad press” about this cartridge due to people not representing the calibre correctly. Many misconceptions are out there about where this load fits in the whole scheme of things. This article really gives great information on the .300 Weatherby and explains where it might fit into your rifle collection.

******************************************************************************

.300 Weatherby Magnum

History

Based on the .300 H&H case blown out to maximum capacity, the .300 Weatherby Magnum was introduced by Roy Weatherby in 1944. Although the case design of the Weatherby was entirely different from the .300 H&H, enabling head spacing at the shoulder, Weatherby retained the belt at the case head, resulting in a very successful marketing ploy. The .300 Weatherby became the most popular cartridge of the Weatherby line and historically, is responsible for initiating the general trend towards ultra velocity cartridges.

In 1963 Winchester released their .300 Winchester magnum as competition to the Weatherby cartridge. The Winchester offering had two major advantages, inexpensive factory ammunition along with plainer, more utilitarian rifles as opposed to the Weatherby rifles which at this time, were often considered somewhat garish in appearance by many shooters. The Winchester cartridge and rifles appealed to more reserved hunters, the Weatherby to those that favored extreme velocities. Although the .300 Winchester Magnum became a major worldwide success, it took only a small share of Weatherby’s market, each style of rifle and cartridge appealing to different customers.

Today, the Weatherby remains popular as a medium game hunting cartridge but has come into its own as a long range hunting cartridge, utilized in both both factory and custom rifles. One could say that in this regard, the .300 Weatherby was 50 years ahead of its time as it has only been recently that suitable optics and range finders for long range hunting have been available to the public at affordable prices.

Performance

The .300 Weatherby Magnum is a truly powerful, highly effective medium game cartridge. This cartridge has however always suffered one major limitation – unrealistic expectations. In earlier years the Weatherby was promoted as being able to flatten anything that walked via sheer velocity. Extreme advocates of the .300 Weatherby have over the years made strongly convincing statements of this cartridges ability to cause such wounding that animals may be “blown in half” and that accordingly, shot placement when using the Weatherby is of low priority. Unfortunately, in many instances, the factors of bullet construction and precise shot placement were abandoned in favor of fantastical reasoning.

In Africa, guides shuddered at yet another client toting a .300 Weatherby, another potential bullet blow up, a failed or slow kill resulting in hours of tracking and hard labor. In the South Island of New Zealand, shots would have to be taken at 300-400 yards, a challenge in the days before high power optics, range finders and drop charts. NZ guides would watch as shot after shot went down range at the nimble Thar and Chamois, the hit rate was low, gut shots were common. The term ‘Weatherby eyebrow’ also became common, a problem associated with short eye relief scopes on high recoiling rifles. Clients often had more of a chance of wounding themselves than their intended target. North American guides and Canadian guides had exactly the same experiences. All of this gave the .300 Weatherby a bad reputation which stuck for decades.

The strengths of the .300 Weatherby lie in its ability to produce effective killing on a wide variety of game species and body weights, out to ranges well beyond 1100 yards (1km). However, the .300 Weatherby cannot do all of these things with a single load, nor can it shoot itself.

The .300 Weatherby Magnum can only be exploited through accuracy combined with appropriate projectiles for the job at hand. .300 Weatherby shooters must learn to be able to differentiate between rifle accuracy problems and shooter error. Practice is key if any level of proficiency is to be obtained. In platforms which induce intolerable or uncontrollable recoil, a muzzle brake should be fitted to aid accuracy.

Choice of optics for .300 Weatherby rifles is also very important in order to avoid the dreaded Weatherby eyebrow (scope cuts to the eyebrow) and the flinch that develops both before and after injury. Short eye relief scopes should be avoided and shooters need to understand that short eye relief scopes can be found within most brands (including high end optics such as Zeiss and Swarovski). When selecting a scope, the shooter must observe ‘models’ rather than brands to obtain correct eye relief information. Appropriate scope eye relief for the .300 Weatherby (actually all of the .300 Magnum family) unbraked is 4”.

Loaded with 150 grain bullets, the .300 Weatherby is a spectacular killer of lighter medium game. Penetration can occasionally be somewhat poor with conventional projectiles when used at closer ranges on large bodied animals. In general, on light game weighing 40 to 60kg (up to 130lb) 150gr conventional or premium bullets driven at 3450fps produce a wound channel through vitals of between 2 and 3” in diameter, resulting in exit wounds of the same diameter, when used at close to moderate ranges. On game weighing between 60 and 90kg (130-200lb), internal wounds may be 2-3” in diameter, however 150 grain conventional bullets may or may not exit depending on bullet construction and bone encountered. Premium 150 grain bullets such as the Nosler Partition, Scirocco and InterBond will in most instances exit, rendering a 1.5 to 2” exit wound. A 150gr bullet does provide some room for error when matched appropriately to game weights.

In the .308 Win and .30-06, traditional 165 grain hunting bullets quite often produce clean but delayed killing on light framed game. Accordingly, one might expect that the velocities of the Weatherby would ensure more emphatic results. Unfortunately, this does not prove true, at least not in a uniform and predictable manner, especially at extended ranges where cartridge performance overlaps. While some bullet designs such as the 165 grain SST can prove to be spectacular killers of light framed or lean game, often the results are the same as those derived from the .308 Win and .30-06. Again, the 165 grain bullet weight proves its merit when used on medium body weights of between 80 and 150kg (180-330lb). Such results also help us understand that the immense power of the Weatherby is best utilized as a means to obtain fast killing at extend ranges, not increase killing power within ordinary hunting ranges (300 yards). As stated however, there are exceptions, the Hornady 165 grain SST is immensely and positively responsive to increased velocities.

Loaded with 180 grain bullets the Weatherby is an emphatic killer of larger bodied medium game out to generous ranges. The Weatherby places great stress on projectiles, demanding that bullet construction be matched to game weights in order to avoid erratic or unexpected disappointing results. On game weights of between 90 and 300kg (200-700lb) wound channels produced by appropriate 180gr bullets driven at 3250fps tend to be around 1.5 to 2” in diameter. Conventional 180gr projectiles produce similar sized wounds to premium 180gr bullets but at Weatherby velocities are extremely prone to gradual and total disintergration, rapidly decreasing the depth of wounding at close ranges.

Many 180gr to 200gr .30 caliber bullets driven at Weatherby velocities are close to ideal for use on Elk simply because the thickness of the shoulder corresponds with the distance traveled before many 180 to 200gr bullets (both conventional and premium) reach full wounding potential. The width of an Elk chest corresponds with the distance most 180 and 200gr bullets travel while creating the broadest part of their wound channel. The wound channel gradually tapers to a size not much bigger than the mushroomed projectile as it comes to rest or departs the skin of the offside shoulder.

When enough resistance is met, 180 to 200 grain bullets may bore an internal wound through vitals of approximately 2 to 3” in diameter. On lighter game however; wounding with 180-210 grain bullets tends to be much smaller, around 1”, with little or no hydrostatic shock, greatly decreasing room for error, regardless of muzzle velocities or range. At longer ranges where velocities approach those of the .308 Winchester (around 300 yards), room for error drops substantially and accurate shot placement is paramount. Rifles that cannot shoot 1 MOA or less at 100 yards may cause slow killing and in precipitous country this often results in the frustration of an un-retrievable animal that has tried to escape into safe inaccessible terrain but died in the process.

Loaded with 200-220 grain bullets, the .300 Weatherby can be utilized to great effect on very large game. Again, bullet construction is of immense importance when using the Weatherby on tough game. On game such as Grizzly bear, the heavy Swift A-Frame and Woodleigh bullets are bread and butter, producing highly traumatic wounding and deep penetration for fast, clean and humane killing. On truly heavy game, the .30 calibers, regardless of muzzle velocity, lack the ability to produce deep broad wounding with ordinary cross body shots. On heavy game, neck and head shots with premium projectiles produce emphatic results.

Loaded with heavy, frangible, high BC projectiles, the .300 Weatherby is an excellent long range hunting cartridge filling a game performance niche that no other cartridge apart from the .300 Dakota fills. Case capacity of the Weatherby is about as large as this bore diameter can handle (gas expansion) without going overboard towards the realms of extreme bullet jump and severely shortened barrel life. While the freebore of the Weatherby is long, the equally long case neck acts as a reliable guide, having more in its favor than the .308 Winchester freebore design. Loaded with heavy frangible bullets, the Weatherby can be expected to produce fast killing on a wide variety of body weights out to ranges exceeding 1100 yards.

The strengths of the .300 Weatherby (and .300 Magnum family) can be found when used on game weighing between 90 and 320kg (200-700lb) at ranges of 300 yards and beyond, achieving results that cannot be found in the sevens and smaller calibers, regardless of down range trajectories. The trade off is recoil. The .300 Weatherby produces a level of recoil that must be tamed through either design and technology or technique and personal discipline, in order to obtain optimum results.

Factory Ammunition

Light weight loads from Weatherby include the 130 grain Barnes TTSX at 3650fps, the 150 grain Hornady soft point Interlock and the 150 grain Nosler Partition at 3540fps (26” barrels). Due to the twist rate of 1:10 utilized in Weatherby factory rifles for optimum accuracy with heavy bullets, while some rifles may produce excellent accuracy with 130-150 grain bullets, results vary.

The 130 grain TTSX bullet is a relatively new offering from Weatherby and although its weight may seem negligible, 130 grains is about perfect for a homogenous .30 caliber bullet for use on light through to medium weight antelope and deer species along with wild boar. This load is perfectly adequate for tackling game weighing up to 150kg (330lb), rendering broad internal wounding for fast killing, yet often showing minimal meat damage as velocities fall below 3000fps. The 130 grain TTSX does its best work at impact velocities above 2200fps or approximately 500 yards.

The 150 grain Hornady Interlock is best suited to light game under conditions where raking shots do not have to be taken at close ranges, producing best results between the ranges of 125 and 425 yards. Beyond 425 yards, wind drift starts to become a problem for the Interlock (and Partition). The 150gr Partition is an excellent projectile for use on game weighing up to 100kg (220lb) and at ranges beyond 125 yards, is adequate for game weighing up to 150kg. If the 150 grain Partition is pushed too hard, such as on large tough animals at close ranges, there is a small risk of jacket / rear core separation. The Partition is a stellar performer, producing wide, violent wounding for fast killing but hunters must be realistic about limitations. Sectional density versus game weights must always be taken into consideration when using the Partition. The 150 grain Partition produces excellent wounding down to velocities of 1800fps (750 yards) however wind drift is a major limiting factor.

Weatherby currently list three 165 grain loads including the Interlock (flat base) at 3390fps, the 165 grain Ballistic SilverTip at 3350fps and the 165 grain Barnes TSX at 3330fps. The 165 grain Hornady projectile has a much softer jacket than the Ballistic SilverTip. Best suited to game weighing up to 90kg if used at woods ranges, the Interlock produces its most uniform results on game weighing between 80 and 150kg (180-330lb) at impact velocities of between 3100 and 2200fps (between 100 and 500 yards) though still showing vivid expansion at 2000fps. This is a good, fast killing load, suitable for a vast range of deer species and should not be overlooked.

The 165 grain BST is a flat shooting projectile with a BC of .475 as opposed to .387 for the Interlock. However; as ranges are increased, the BST can produce delayed killing (regardless of excellent wounding) on lean game (under 90kg/180lb) with rear lung shots. In contrast, the Hornady bullet would have produced slightly delayed killing, rather than a long ‘dead run’. Both of these 165 grain bullets are immensely useful but there is a definite requirement to match game weights to bullet construction. The subtleties of this can be difficult to explain. For example, the BST is frangible at close ranges but the slight delay (perhaps only .5” of penetration) can inhibit hydrostatic shock transfer (see game killing text) via the ribs to the spine and through to the brain. So while internal wounding can be broad, lean game may run, in some cases being lost in ravines (a curse of alpine hunters). As body weights increase slightly, tipping my often quoted 90kg (180lb) mark, the target resistance is matched to bullet expansion, resulting in very emphatic killing.

Weatherby’s tough 165 grain TSX load has its strengths, suitable for game weighing between 90 and 320kg (180-700lb). On large animals, especially at impact velocities below 2600fps, hydrostatic shock can be non-existent and wounding can be a little narrow. Again, best results are obtained by matching body weights to bullet construction.

Weatherby 180 grain offerings include the Hornady Interlock (flat base) at 3240fps, the BST at 3250fps, the Partition at 3240fps, the Accubond at 3250fps and the 180gr Barnes TSX at 3240fps. Weatherby’s 180 grain loads are best suited to game weighing above 90kg (180lb). The five loads offer varying rates of expansion, suitable for a wide variety or game weights of up to 450kg (180-1000lb).

The 180 grain Interlock and BST loads are, like the 165 grain loads, best suited to game weighing between 90 and 150kg but at extended ranges of around 300 yards and beyond, can be very emphatic on game weighing up to 320kg (700lb). Put simply, increasing range increases bullet performance on larger bodied animals.

The 180 grain Partition is a versatile bullet, rendering deep, broad wounding on game weighing up to 320kg (700lb) and is about ideal for Elk. From a muzzle velocity of 3240fps, the Partition can be expected to produce deep, broad wounding down to 1800fps or 780 yards. The Partition can be asked to tackle larger body weights of up to 450kg (1000lb) but not at woods ranges with ordinary chest shots due to the risk of jacket / rear core separation should the Partition strike ball joints. As with all of the .30’s, on heavy game, neck and head shots ensure emphatic results, minimizing incidents of insufficient penetration (such as the close range/ball joint example). At longer ranges, the Partition shows adequate penetration on heavy game but, due to the limitations of the bore diameter, can produce narrow lung wounding (proportionate to game weights). As always, readers are advised to study and record autopsy results, take photo’s, monitor wounding and penetration in order to provide sound conclusions.

Weatherby’s 180 grain Accubond load is ideally suited to game weighing between 90 and 320kg out to ranges of around 575 yards. Somewhat of an oddity, the Accubond will often produce delayed kills on lean game due to the slightest delay in expansion (minimal target resistance) yet at the other extreme, when the Accubond encounters too much body weight, it suffers severely limited penetration and wounding. This is one of many projectiles that are about ideal for ridge to ridge shooting of Red deer, Mule Deer, Caribou, Himalayan Thar and at the upper end, Elk.

For tough game, the 180 grain Barnes TSX at 3240fps is a good performer. It is definitely true that the faster the Barnes is driven, the better, working well with the Weatherby ethos. Ideally suited to game weighing above 150kg (330lb), the TSX produces violent wounding for fast killing out to ranges of around 300 yards, steadily declining in wounding potential thereafter. On truly large heavy game, the 30 caliber TSX can produce narrow wounding, regardless of full cross body penetration. Again, this is a limitation of the bore diameter, not the bullet design.

Weatherby list two heavy loads, the 200gr Partition at 3060fps and the 220gr Hornady round nose bullet at 2845fps. The 200 grain Partition is a very versatile bullet, boasting an excellent balance of high SD versus high velocity, versus fast expansion, essentially ticking all of the boxes. Yet still, this load does not make the .300 Weatherby ideal water buffalo medicine. Great strengths combined with realistic expectations are the key. This load is very well suited to North America and Canada’s large game species, at both close ranges as well as long ranges of up to 700 yards or so (1800fps). Deep, violent, highly traumatic wounding are hall marks of the 200 grain Partition driven at high velocity. Weatherby’s heaviest load, the 220 grain Interlock is unfortunately, a lack luster performer on large animals. This is an extremely soft jacketed projectile, more suited to game weighing up to 150kg (330lb) at woods ranges. Used this way, the 220 grain Interlock load displays great strengths.

Remington currently list one load for the Weatherby, the 180gr Core-Lokt at 3120fps. The economical Core-Lokt is an excellent 90 to 180kg (200-400lb) game bullet and is less prone to blow up than the 180gr Interlock, also producing adequate performance on large body weights of up to 320kg (700lb) as velocities fall below 2800fps (125 yards). The Core-Lokt has a low BC of .383, losing velocity rapidly and suffering wind drift accordingly, producing best performance inside 400 yards.

Federal currently list three180gr loads for the Weatherby, the 180 grain Partition at 3190fps, the 180gr Trophy Bonded Bear Claw (now featuring a polymer tip) at 3100fps and the 180 grain TSX at 3110. As has already been described, the Nosler partition is an excellent projectile, about ideal for Elk. The TTBBC offers a unique level of performance that cannot be under-estimated. This projectile has the ability to render heavy trauma throughout penetration, producing emphatic and ‘safe’ kills on tough game. The TTBC has a BC of .480, not exceptionally high but great enough to deliver immense trauma out to a range of 250 yards, retaining good performance out at 350 yards (2400fps). Below 2400fps, wounding gradually becomes narrower, more so and especially at 2200fps and below. It is odd that Federal list the TSX alongside the TTBBC loading, overlapping performance. A frangible long range projectile such as the Speer 180 grain BTSP would add more versatility to the Federal line up.

Hand Loading

As a hand loading proposition the .300 Weatherby has had a somewhat jaded past. Most hand loaders and powder manufacturers working up loads in the Weatherby, from the 1950’s through to the 1980’s, were either unable or unwilling to try and achieve Weatherby’s advertised velocities and instead, loads duplicated what hand loaders were already achieving in the .300 Win mag with figures of 3300 and 3070-3100fps with 150 and 180gr bullets respectively. Throat lengths also tended to vary from the generous free bore of the Mark V rifle to short throated designs, created towards a goal of optimum accuracy. It was also very common for hunters to dock the 26” barreled Mk V to 24” to make the rifles more portable. The Weatherby needs a 26” barrel, not just for velocity but also to keep weight, noise and muzzle blast forwards. Longer barrel lengths also show great strengths in these areas.

From a Factory standard 26” barrel, realistic velocities for the .300 Weatherby include 3450fps with 150gr bullets, 3300fps with 165-168gr bullets, 3250fps with 178-180gr bullets, 3150fps with 190 grain bullets, 3050fps with 200 grain bullets, 3000fps with 210 grain match bullets and 2900fps with 220 grain bullets. Individual rifles can achieve higher velocities than the above stated figures. In half throated custom barrels, velocity loss is in the order of 100fps, though again, individual rifles vary.

Twist rate of the .300 Weatherby is as mentioned, typically 1:10, ideal for bullet weights of 165 grains and heavier. In such instances where a light, fast expanding bullet is desired but accuracy is poor, bullet designs like the Hornady 178 grain A-Max are capable of achieving optimum results on light game.

Rather than continually reiterating bullet performance at magnum velocities, the section ahead will focus on some of the more effective projectiles that allow the .300 Weatherby to truly shine.

Of the Hornady bullet range, the light 150 grain SST and Interbond can be used to great effect on lighter game. The one limitation with the 150 grain SST, is that at close ranges where velocity is high, the projectile can sometimes meet too much resistance (water surface tension), failing to impart hydrostatic shock. On light framed game, regardless of whether bullet blow up occurs (due to ultra velocities), wounding through vitals is always thorough. The negative aspect of the SST is more to do with expectations than anything else, the disappointment of slightly delayed killing. The 150 grain Interbond does not produce this type of reaction at close ranges and, where these odd instances of hydrostatic shock failure do occur, the two projectiles can be used together, the InterBond for very close range work while being equally good out to ranges of around 350 yards, the SST coming into its own at 3200fps (after 100 yards).

The 165 grain Hornady SST driven at 3300fps is a violent, emphatic killer of medium game, a generally exceptional deer bullet. Again, this 165 grain bullet does its best work on game weighing between 80 and 150kg (180-330lb) with one caveat, by keeping the SST above 2400fps out to a range of 425 yards, speed of killing is increased on very light framed game where rear lung shots are taken. This makes for a very versatile, effective and emphatic deer bullet in the Weatherby. Along with this, the 165 grain Interbond can be partnered with the SST and used to great effect on body weights of 90-200kg (200-330lb), giving best performance out to the same quoted range of 425 yards.

Expectations are key when using the 180 grain SST on game in the Weatherby. When used at ordinary hunting ranges, this projectile does its very best work on game in the 80 to 150kg range, just the same as the 165 grain SST. The 180 grain SST can also be a spectacular killer of light framed game at impact velocities above 2600fps. If the 180 grain SST is used at ranges of 50-100 yards on game weighing 80-150kg, killing is fast and emphatic, yet penetration is often less than expected, the projectile coming to rest against offside skin. As velocity falls, performance is enhanced, wounding on raking shots is deeper, though the ogive of the 180 grain SST should be annealed (rotated) in candle flame for best results. On deer/antelope species weighing around 320kg (700lb), the 180 grain SST gives best performance between the velocity parameters of 2600 and 1600fps or approximately 300-950 yards. The tough 180 grain InterBond is as can be expected, an emphatic killer of large bodied deer out to moderate ranges.

Hornady’s 178 grain A-Max can be used not just as a long range bullet, but as an alternative to the 150 grain bullet for use on light game. The 178 grain A-Max is an excellent performer on lighter body weights but on game weighing 90kg and heavier, is much more effective at longer ranges. Generally speaking, the 7mm and .30 caliber A-Max projectiles display best penetration at impact velocities of 2600fps and below. On tough game, there is a marked decrease in penetration at impact velocities of above 2900fps.

As a long range hunting cartridge, the .300 Weatherby loaded with the 208 grain A-Max is a powerhouse. The 208 grain bullet produces immensely traumatic wounding right down to the typical 1400fps that is often quoted within this research. At low velocities, frontal shots on light framed game should be avoided, simply due to the wastage of the entire carcass. From a muzzle velocity of 3000fps (some rifles achieve higher velocities), the 208 grain A-Max travels around 1325 yards before breaking the 1400fps, reaching the sound barrier (standard atmospheric model) at a whopping 1730 yards. The 208 grain A-Max is ideal for a vast range of game, reaching its practical limits on Elk.

Speer’s traditional Hotcor and BTSP projectiles can be very useful in the Weatherby. The 150 grain Hotcor is a spectacular killer of light game within ordinary hunting ranges. The 150 grain BTSP is however, much too soft, if close range shots are encountered. The middle weight 165 grain Hotcor and BTSP both show great strengths, again on the body weights of 80-150kg (180-330lb). The 180 grain Hotcor, though so very basic in its design, is a hard hitting bullet, ideal for large bodied deer. The soft, highly frangible 180 grain BTSP also has great strengths and with its high BC of .545, can be used out to very long ranges. This is a bullet that excels on game weighing between 90-180kg (200-400lb) out to ranges of 900 yards (1800fps), continuing to produce adequate wounding on suitable body weights, as velocities fall to 1600fps. The 200 grain Speer Hotcor is a wonderful projectile, hard hitting and clean killing, ideal for large bodied deer and especially useful for woods hunting. BC of the 200 grain Hotcor is .478, delivering highly traumatic wounding out to ranges of around 350 yards.

As discussed in the factory ammunition section, the Nosler Partition projectiles are excellent performers producing fast, violent expansion down to 1800fps, along with excellent penetration. In many instances, performance is more spectacular and more uniform that either the Ballistic Tip or Accubond bullet designs. That said, the 150 grain Accubond produces outstanding results on light game, out to ranges of around 400 yards. The 180 grain Accubond is a stellar performer on larger bodied deer but on deer species weighing around 320kg (700lb), the 200 grain Accubond really comes into its own in the .300 Weatherby. The heavy Accubond is, like its kin, prone to shed as much as 50% of its weight after impact but offers a high BC, fast expansion, broad wounding and desirable penetration. This is an excellent cross valley hunting bullet.

Nosler’s 180 and 200 grain Partition bullets show great strengths on Elk sized game, but cannot be expected to produce entirely uniform results with chest shots on heavy game where the foreleg bones are 3” in diameter and the ball joints are of 5” in diameter or larger. The heaviest of the Partitions is the 220 grain semi point, capable of excellent penetration, again, not ideal for bovine sized game with chest shots but certainly effective on body weights of up to 400kg (880lb), tackling heavier game with ease if head and neck shots are employed.

Of the core bonded bullet designs for use on tough game, Woodleigh (Protected Point) and Swift (A-Frame) produce stellar performers. These two brands should always be the first consideration when hunting tough game, both offering 200 grain bullets, capable of withstanding magnum velocities with ease. These projectiles work extremely well at high impact velocities and the .300 Weatherby has no trouble keeping velocities well above 2400fps out to 300 yards or so. Swift also produce the highly traumatic Scirocco projectiles which are emphatic killers when bullet weights are matched to game weights accordingly.

Barnes bullets, as mentioned in the factory ammunition section, have great strengths and Weatherby have a great load in the 130 grain offering. The only negative aspect, is that the combination of the 1:10 twist rate, freebore and ultra velocities can prevent some rifles from being able to obtain optimum accuracy. Nevertheless, in rifles that produce desirable accuracy, the 130 grain TSX is a hard hitting, deep penetrating bullet, ideal for goat, deer and boar. As bullet weights are increased, penetration increases.

Barnes projectiles like to be put to work, the harder the Barnes TSX is made to work the better with 150 grain bullets working well on 150kg animals and 165-168 grain bullets on 200-320kg (440-700lb) animals. The 180 and 200 grain Barnes bullets are to some extent limited by the bore diameter, a somewhat difficult factor to explain, more easily recognized in the field. The heavy TSX bullets are capable of full cross body penetration on large, heavy game, but, regardless of muzzle velocities, wound channel diameters are not nearly as wide as is produced in the wider bores. The .358 225 grain TSX driven at mild velocities of 2500fps helps paint the full picture very clearly. But as a rule of thumb for the 180-200 grain Barnes 30 caliber TSX bullets, heavy body weights are the key, delivering fast killing on body weights of up to 400kg (880lb) at impact velocities of above 2400fps. As body weights approach 600kg (1300lb), regardless of exit wounding, delayed killing can be expected, limited by bore diameter, not bullet design.

Berger’s 175-210 grain VLD projectiles are very useful in the Weatherby for long range hunting. These projectiles produce frangible wounding in the absence of high velocity (in the absence of disproportionate to caliber wounding) but do require that bullet weights be matched to game weights in order to initiate full fragmentation. The current 175, 185, 190 and 210 grain VLD designs work best on game weighing between 90 and 180kg (200-400lb) with the 210 grain VLD continuing to produce good performance on heavier body weights of up to 320kg (700lb). Full fragmentation can be expected at velocities as low as 1400fps. In instances where game encountered are much leaner than expected and where no bone is hit (liver shots), the cut off point for full fragmentation can be as high as 1800fps. Fortunately, the .300 Weatherby does its best to help, launching the VLD bullets at extremely high velocities, aiding retained velocity down range.

Closing Comments

Nearly 60 years on, the .300 Weatherby is finally coming into its own, thanks largely to bullet designs and optics, capable of utilizing the impressive velocities produced by this cartridge. Along with this, Weatherby now offer true long range rifles featuring full contour barrels and suitable stock designs.

This cartridge is a highly emphatic and often spectacular killer of medium game, tackling a wide range of body weights under a variety of conditions. Realistic expectations are the key to great success when using the Weatherby. Optimum performance can only be achieved through accuracy and unlike a more mild .30, such as the .308 Winchester, the Weatherby and its .300 magnum kin call for a greater level of attention and awareness towards both rifle accuracy and shooter technique. A poor shot with the .300 Weatherby is far less effective than a single and perhaps rather easily well placed shot with a .308. But when it all comes together, an accurate rifle chambered in .300 Weatherby Magnum, suitable projectiles and optimum technique, well that’s something.

| Suggested loads: .300 Weatherby Magnum | Barrel length: 26” | |||||

| No | ID | Sectional Density | Ballistic Coefficient | Observed MV Fps | ME Ft-lb’s |

|

| 1 | FL | Wby 130gr TTSX BT | .196 | .350 | 3650 | 3845 |

| 2 | FL | Wby 150gr Partition | .226 | .387 | 3450 | 3964 |

| 3 | FL | Wby 180gr Partition | .271 | .474 | 3240 | 4195 |

| 4 | FL | Wby 200gr Partition | .301 | .481 | 3060 | 4158 |

| 5 | HL | 165gr SST | .248 | .447 | 3300 | 3989 |

| 6 | HL | 178gr A-Max | .268 | .495 | 3250 | 4174 |

| 7 | HL | 180gr Accubond | .271 | .507 | 3250 | 4221 |

| 8 | HL | 200gr Woodleigh PP Mag 200gr A-Frame | .301 | .450 | 3050 | 4130 |

| 9 | HL | 200gr Accubond | .301 | .588 | 3050 | 4130 |

| 10 | HL | 208gr A-Max | .313 | .648 | 3000 | 4156 |

| Suggested sight settings and bullet paths | |||||||||

| 1 | Yards | 100 | 200 | 341 | 382 | 400 | 425 | 450 | 475 |

| Bt. path | +3 | +4.5 | 0 | -3 | -4.6 | -7.1 | -10 | -13.3 | |

| 2 | Yards | 100 | 175 | 322 | 362 | 400 | 425 | 450 | 475 |

| Bt. path | +3 | +4.2 | 0 | -3 | -6.5 | -9.3 | -12.5 | -16 | |

| 3 | Yards | 100 | 175 | 307 | 349 | 375 | 400 | 425 | 450 |

| Bt. path | +3 | +4 | 0 | -3 | -5.3 | -7.9 | -10.8 | -14.1 | |

| 4 | Yards | 100 | 175 | 282 | 323 | 350 | 375 | 400 | 425 |

| Bt. path | +3 | +3.7 | 0 | -3 | -5.6 | -8.3 | -11.4 | -14.9 | |

| 5 | Yards | 100 | 175 | 310 | 352 | 375 | 400 | 425 | 450 |

| Bt. path | +3 | +4.1 | 0 | -3 | -5.1 | -7.7 | -10.7 | -14 | |

| 6 | Yards | 100 | 175 | 307 | 349 | 375 | 400 | 425 | 450 |

| Bt. path | +3 | +4 | 0 | -3 | -5.3 | -7.9 | -10.8 | -14.1 | |

| 7 | Yards | 100 | 175 | 308 | 350 | 375 | 400 | 425 | 450 |

| Bt. path | +3 | +4 | 0 | -3 | -5.2 | -7.8 | -10.7 | -13.9 | |

| 8 | Yards | 100 | 150 | 278 | 317 | 350 | 375 | 400 | 425 |

| Bt. path | +3 | +3.7 | 0 | -3 | -6.1 | -8.9 | -12.2 | -15.9 | |

| 9 | Yards | 100 | 160 | 287 | 329 | 350 | 375 | 400 | 425 |

| Bt. path | +3 | +3.8 | 0 | -3 | -4.9 | -7.4 | -10.3 | -13.6 | |

| 10 | Yards | 100 | 160 | 283 | 325 | 350 | 375 | 400 | 425 |

| Bt. path | +3 | +3.7 | 0 | -3 | -5.3 | -7.8 | -10.8 | -14.1 | |

| No | At yards | 10mphXwind | Velocity | Ft-lb’s |

| 1 | 400 | 12 | 2518 | 1830 |

| 2 | 400 | 11.5 | 2457 | 2010 |

| 3 | 400 | 9.2 | 2496 | 2490 |

| 4 | 400 | 10.5 | 2308 | 2366 |

| 5 | 400 | 10.3 | 2455 | 2207 |

| 6 | 400 | 9.4 | 2488 | 2446 |

| 7 | 400 | 9.1 | 2505 | 2507 |

| 8 | 400 | 11.6 | 2243 | 2233 |

| 9 | 400 | 8.4 | 2427 | 2616 |

| 10 | 400 | 7.7 | 2437 | 2743 |

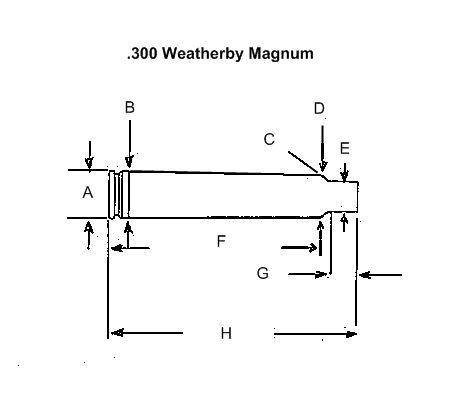

| .300 WBY | Imperial | Metric |

| A | .532 | 13.51 |

| B | .512 | 13 |

| C | R.151 | |

| D | .492 | 12.5 |

| E | .336 | 8.53 |

| F | 2.504 | 63.6 |

| G | .321 | 8.15 |

| H | 2.825 | 71.76 |

| Max Case | 2.825 | 71.76 |

| Trim length | 2.815 | 71.46 |

***************************************************************************

After reading this article, I fully intend to work on solid loads in other bullet weights as well. Having the added variances for hunting different sized animals sounds like a great way to go. This is especially so since this article explains and matches bullet channel information with different bullet weights compared to different sized animals.

I liked this article and will definitely be looking over this site for other interesting articles on other calibres.